Picture this. You are walking down a busy street when you get a text message from a close friend. It’s a funny message, so you respond immediately, and the two of you engage in a fun back-and-forth. You are so absorbed in the conversation that, when it’s time to cross the street, you don’t even think to check if any cars are coming. As soon as you step into the street, a fast bus passes in front of you loudly honking . Fortunately, you are safe and sound, but the scare that you got certainly made you look up from your phone. You feel your heart pounding,your hands sweating. Someone stops to ask if you’re okay and they notice how large your pupils look.

In moments of intense emotion like this, these bodily reactions become very noticeable to you. But the truth is, your body is always reacting to what is happening in and around you, even when you don’t notice. This happens because of the autonomic nervous system—the branch of your nervous system that controls bodily functions and works mostly unconsciously and involuntarily. It has two branches of its own: the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The first one is known as the fight or flight system because it is activated in situations of stress, like when you almost have a traffic accident. The parasympathetic system is related to relaxation responses, for example when the scare is over and you are returning to a more regular state.

Look at your heart rate, for example, which went up when you were afraid. Both sympathetic and parasympathetic branches influence heartbeat, but with opposing effects and to different degrees depending on the circumstances. As you can probably deduce by now, the sympathetic system (the fight or flight branch) increases heart rate, whereas the parasympathetic system decreases it. Because both systems are always active to a certain extent, your heartbeat is never constant: it is always varying slightly—and sometimes not so slightly. This is what makes it flexible, so that your heart can respond to situations quickly. In fact, how much your heart rate varies during rest is a measure of how responsive your heart is to changes in your environment. Heart rate variability does not only indicate how well your heart reacts to the environment, it may also relate to the emotional and psychological state of a person. Low levels of heart rate variability (that is, when your heart rate doesn’t fluctuate much, but stays more constant) are related for example to deficits in a person’s ability to regulate their emotions. It has also been associated with depressive and social anxiety disorders [1, 2].

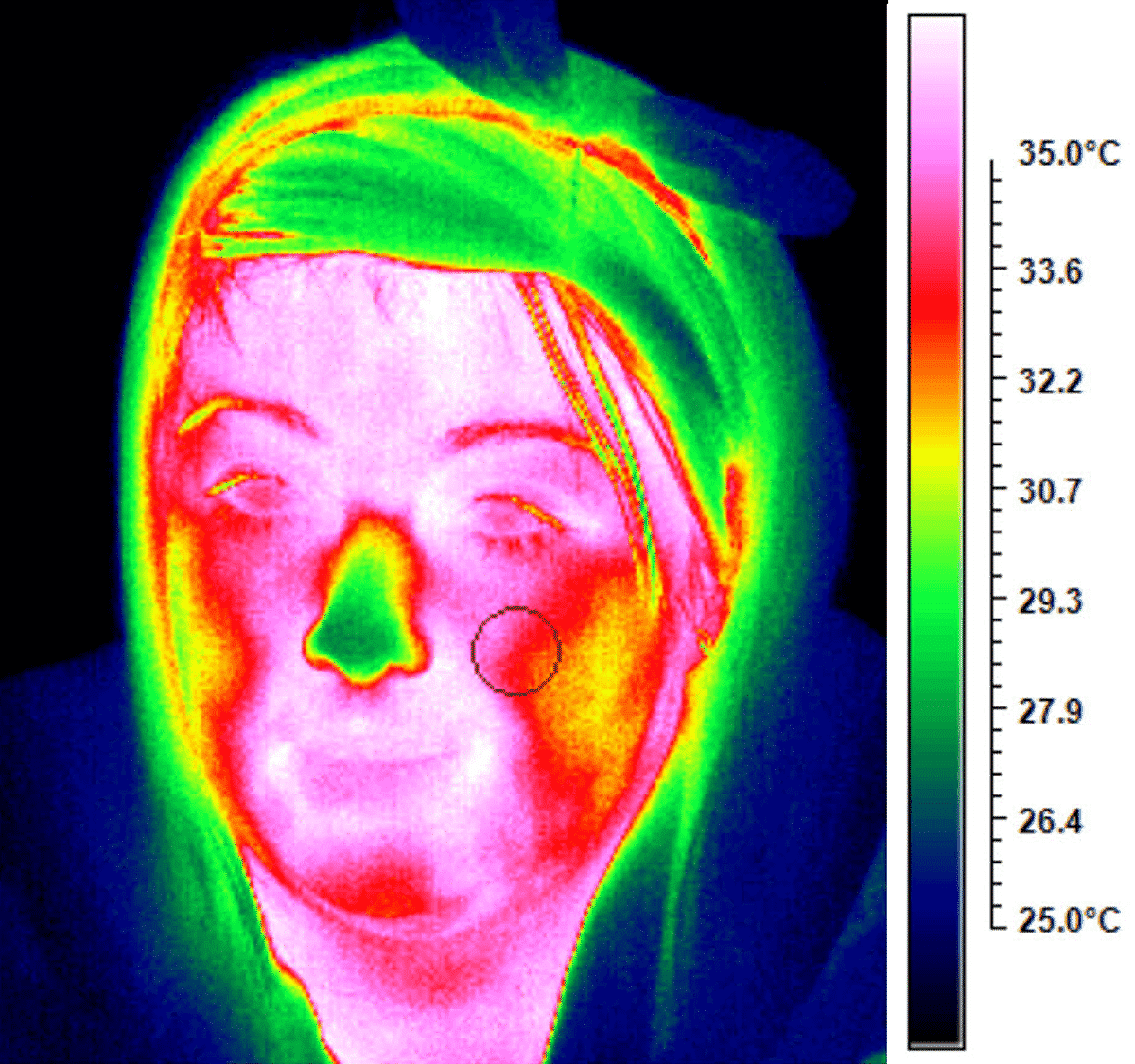

Another example of how your body responds to the environment are the changes in your skin temperature. These changes can happen because of the constriction of veins right under the skin in situations of stress; because of emotional sweating; or because of the involuntary activation of face muscles, which influences where blood (which is warm) flows. Researchers have found some interesting things about behavior and skin temperature. For example, in a study at Tilburg University, scientists asked participants to play a virtual ball game with two other people. Some of these participants were never thrown the ball—that is, they were made to feel excluded from the game. In these cases of social exclusion, the temperature in their fingertips tended to decrease throughout the course of the experiment [3]. Interestingly, in another experiment, the researchers also saw an effect in the opposite direction. When participants were made to feel physically warmer (with a warm beverage or in a warm room), they reported to feel socially closer to another person than when they were made to feel physically colder. In fact, even their language use changed: in warmer conditions, they tended to use more concrete (instead of abstract) language when describing a video clip [4].

These are just two quick examples of the close relationship between our psychological state (what we think, feel, say) and our physiology—how our bodies function. This type of relationship can be found not only in heart rate and body temperature, but also in many other physiological processes—our breathing, the electrical activity of our skin, our eye movements and pupil dilation to name a few. Maybe the saying “mind over matter” isn’t completely accurate. Perhaps mind and matter aren’t as disconnected as we may think.

Follow us on Twitter (@CobraNetwork) and Instagram (@conversationalbrainsmscaitn) to stay up to date.

Author: Tom Offrede, ESR5, @TomOffrede

Editors: Lena Huttner, ESR 1 @lena_huttner

Feature image taken from Ioannou, S., Morris, P. H., Baker, M., Reddy, V., & Gallese, V. (2017). Seeing a Blush on the Visible and Invisible Spectrum: A Functional Thermal Infrared Imaging Study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00525

If you want to know more about our projects and the ESRs working on them, please look under the Training tab.

References

[1] Kemp, A. H., Quintana, D. S., & Gray, M. a, Felmingham, KL, Brown, K., & Gatt, JM (2010). Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: A review and meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry, 67(11), 1067-1074.

[2] Alvares, G. A., Quintana, D. S., Kemp, A. H., Van Zwieten, A., Balleine, B. W., Hickie, I. B., & Guastella, A. J. (2013). Reduced heart rate variability in social anxiety disorder: associations with gender and symptom severity. PloS one, 8(7), e70468.

[3] IJzerman, H., Gallucci, M., Pouw, W. T., Weiβgerber, S. C., Van Doesum, N. J., & Williams, K. D. (2012). Cold-blooded loneliness: Social exclusion leads to lower skin temperatures. Acta psychologica, 140(3), 283-288.

[4] IJzerman, H., & Semin, G. R. (2009). The thermometer of social relations: Mapping social proximity on temperature. Psychological science, 20(10), 1214-1220.

If you are interested, you can also check out this book, which gives an overview of many other psychophysiological measures, and on which I based a part of this article:

Hardacre, B. (2020). Psychophysiological methods in language research: Rethinking embodiment in studies of linguistic behaviors. Lexington Books.